Lattice-based quantum-safe encryption

February 11, 2024

We all are aware that once quantum computers reach a certain level of capacity (measured in qubits), the encryption standards that we know today will lay bare to them. This means that our communications, transactions, and anything securely transmitted over the internet will be broken by a quantum computer in s feasible amount of time and they can read our messages as if plain text. This matters little for personal privacy as nobody is interested in knowing what I ate for dinner or if someone is having an office romance. Far more valuable things like national transactional systems, communications between the governments, and weapon authentical transmissions are secured by encryption and nobody wants that snooped.

However, we have a new weapon up our belt and that is called quantum-resistant algorithms. They rely on math problems that both conventional and quantum computers should have difficulty solving, thereby defending privacy both now and down the road. We'll briefly touch upon one such algorithm called Kyber and grasp the maths behind it. We'll skip over varied mathematical details (this isn't a research paper, but I'll surely link them below for you to read).

Introduction

When Peter Shor published his Shor's Algorithm, we learned that a large enough quantum computer (likely 20 million qubits) will break all widely used public key systems. To counter this we need a cryptographic algorithm that is as difficult for quantum computers as it is for conventional computers. We'll jump right into the algorithm; I assume you have a working knowledge of cryptography, if not have a look at my earlier blog post.

Kyber

Kyber is a public key encryption system, i.e., it works with a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption. It is also an asymmetric encryption system, meaning encryption is easier than description (if you don't know the private key). To give an intuition about it, we'll start will a simplistic example. But first some rules:

- We'll take modulus to avoid overflow

- We'll take 2 modulus,

q = 17 (suppose)for coefficients and f = x4 + 1 for polynomials. This also guarantees that any polynomial will have a degree less than 4 - We'll introduce some errors in the calculations

Now we are ready! The following are the components of the system:

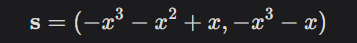

- Private key: s

- Public key: (A,t)

- Error: e

We calculate t = As + e

Encryption

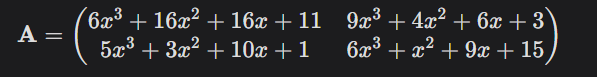

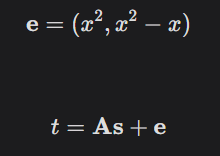

We'll encryption our message using the public key. The encryption procedure uses an error and a randomizer polynomial vector e1, e2, and r, which are freshly generated for each encryption. We'll use the following values:

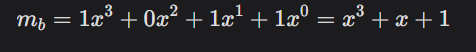

Turning our message into a polynomial using the binary representation. To encrypt 11, we use its binary 1011, giving us:

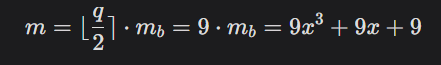

Scale the mb by multiplying it integer(q/2) = 9. Our final message to be encrypted is:

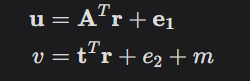

Encrypt m using the public key (A,t) giving us 2 values (u,v) as:

We transmit this data to our recipient and they break it down using the private key. The beauty of this algorithm is that it is damn near impossible for a computer to find the private key.

Conventional computers won't be of any help as we have introduced an error into our systems of equations and no information about the error is transmitted publically, hence there is no better way than to brute force your way into an answer. Neither quantum computer can use superposition of states to evaluate multiple results simultaneously as the computers are ill-fitted to service such a computation. Quantum computing provides no additional benefit in this system.

Decryption

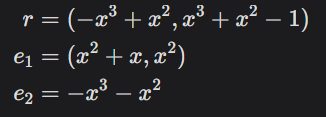

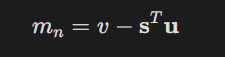

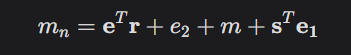

Compute the noisy result:

We scaled m by making the coefficients large, so the coefficients of mn are either close to 9 (implying that the original binary coefficient of mb was a 1) or close to 0 (implying the original binary coefficient was 0).

On computation, the result spits out our original message.

Scaling Kyber

The beauty of Kyber is that it can be scaled by increasing the following parameters:

- n: maximum degree of polynomial

- k: number of polynomials per vector

- q: modulus for coefficients

We observe when we increase n,k to large values and choose arbitrary coefficients to form the public key the computation complexity is equivalent to AES256 for Kyber1024.

Another cool aspect of Kyber is that it is based on Module Learning with Error problems (**MLWE), which can be reduced to the shortest vector problem. So recovering a message from a ciphertext (or a private from a public key) should be as hard as solving a large SVP instance. This should be computationally infeasible, even for a quantum computer. The reduction from Kyber to MLWE to SVP is nontrivial but well-documented. If you are interested in the details I recommend reading Kyber's NIST submission and following the citations.